|

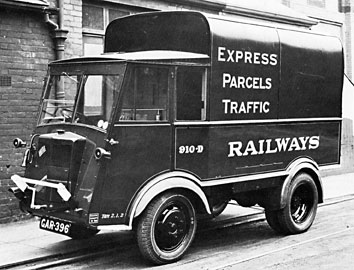

A Karrier 'Bantam' parcels delivery van in wartime livery. Paint date 24.6.1942. |

|

A Karrier 'Bantam' parcels delivery van in wartime livery. Paint date 24.6.1942. |

Before getting involved with the activities of the Road Motor Department, it is necessary in order to set the scene to look at the commercial vehicle industry as it was in the first quarter of this century. Steam vehicle manufacturers tended to supply complete vehicles but the manufacturers of petrol and battery electric propelled vehicles tended to supply only the "Works", that is chassis, engine, transmission, wheels, springing, steering etc., the body work being provided by a body building firm to the customers' specifications. These bodies were usually wood sheeting on a wood framework with the minimum of ironwork usually just hinges, locks and odd bits of strapping.

Prior to the first World War steam vehicles were reliable but only suitable for heavy work. Battery electric vehicles were again reliable but slow. For city work with streets clogged with horse traffic speed was none too important and battery electric vehicles of 15 cwt. to 5 ton capacity were popular with railways for short haul delivery and collection services. Petrol vehicles tended to be an unknown quantity as regard reliability. The best were good but the trouble was finding out which were the best. The production of goods vehicle "Works" was an easy task for any engineering firm while some hit on a sound design, others did not and there was insufficient quantity production anywhere to sort out the good from the bad.

Now the railways were interested and the wonder is that they did not set up their own works to produce the "Works" for their own vehicles. They certainly had a rooted objection to buying in anything other than raw materials, but they did not, and contented themselves by cutting out the body builders and building their own bodies in the carriage and wagon workshops. Before long the design and production of road vehicle bodies and the purchasing of suitable chassis became a department in its own right, with its own organisation headed by a chief engineer. The chief engineers were probably trying to find a safe formula so that they could produce their own works when the first World War broke out. This was a tremendous boon to the manufacturers of sound commercial vehicles as the War proved their designs, eliminated the competition from unreliable designs and provided the market for quantity production which cut the unit cost to a figure so low that no organisation starting from scratch could hope to be competitive. Thus at the end of the War the chief road motor engineers of the various railways had lost all hope of producing their own machines but had a wide choice of battle proved designs available for purchase. Post War purchases were mainly petrol engined vehicles with a few battery electric vehicles more or less to utilise battery charging plants and only the L&Y purchased any quantity of steamers.

The road motor engineer's responsibilities were not confined to purchasing vehicles, providing bodies and then servicing them, he had also to solve various problems that were caused by railways operating road vehicles. The main problem as Always was getting a satisfactory return on investment. Now the road vehicles were designed with the idea of long haul work being important and the railways had a lot of short haul-frequent stops work. This meant that the substantial investment in a motorised vehicle was not being used for most of the time. The vehicles spent more time being loaded and unloaded than moving. There were two ingenious solution to this problem in pre-group days by the Midland and the L&Y. The Midland's solution was to provide separate drays for battery electric chassis. The drays had four legs like a table and at the foot of each leg there was a wheel which could be pinned in either the up or the down position. The chassis was provided with a parallelogram lift and the sequence of operations was thus - load dray, chassis backs under dray, lifts dray, dray wheels pinned up dray dropped in position on chassis, combined vehicle carries out deliveries and collection service, returns to depot, drops off dray for unloading and immediately picks up another loaded dray. Thus the expensive powered chassis was not kept hanging about while loading or unloading took place in the depot. The L&Y solution again involved separate drays but this time the drays were mounted on rollers which located in pairs of channels on the lorry chassis and on some specially fitted drone horse drawn chassis. The operation sequence was:- load dray while stood on horse chassis, move unit from loading bay if necessary by horse, line up lorry chassis and winch dray by hand onto lorry chassis, lock dray in place with catch and commence delivery and collection service, return to depot, transfer dray to drone chassis and pick up loaded dray. This sounds a little more complex than the Midland scheme but in practice proved to be more popular being adopted by the LNWR, LSWR and other railways and being perpetuated by the LMS and remaining in operation up to the end of the thirties.

On the formation of the LMS it could be expected that one of the road motor organisations of the constituents

would take charge of the LMS road motor department. There were three constituants which by volume of

experience were qualified to take over: Midland, L&Y, , and LNWR. To judge by the vehicle body designs

in production just prior to grouping the L&Y and LNWR were both about equal. Both had mounted vehicle

cabs constructed of wood sheeting with glazed windscreen, quarter lights and rear screen and with half cab

doors. The Midland's design on the other hand could best be described as a double width night watchman's hut

with canvas top. Of course the Midland team took over and the early LMS road vehicles mounted Midland type

cabs. The LNWR did, however, have one of its practices adopted and that was dividing the fleet up into

functional types and giving each type a separate fleet number series complete with a suffix letter to

indicate which group the vehicle belonged. The details of these suffix letters are given below.

(A) Steam propelled vehicles.

(B) Petrol (later diesel) propelled vehicles mounting goods bodies i.e. flats, sided, goods vans, livestock

vehicles, tip lorries etc.

(C) Personnel transport, works buses, cars for officials etc. The fleet number was not usually painted on

the vehicle but somewhere inside would be a small oval plate bearing the number.

(D) Delivery vans for express parcels work.

(E) Electric vehicles.

(G) Mechanical horses.

(GT) Trailers for mechanical horses, the GT was not always painted on.

(S) Service vehicles, i.e. non-revenue earning vehicles for road use such as publicity vans.

(T) Trailers (not semi-trailers but full trailers for towing behind lorries or tractors).

(X) Internal use only vehicles not used on public roads, mobile cranes, drone mechanical horses and the like.

Obviously the LMS inherited from the constituants a wide variety of vehicle makes. In the light range there were a substantial quantity of second type Ford T commercials from L&Y, LNWR and Midland and the LNWR and Midland had both made substantial purchases of Karrier 2 to 5 ton vehicles which formed a nucleous of a standardised fleet. The other significant pre-group acquisition was a substantial number of Leyland RAF type lorries from the L&Y some of which lasted in a rebuilt form to be taken over by B.R. The LMS initial purchases were Fords, Karriers and some heavy ADC's (AEC's sold by Daimler) subsequent purchases were made from most, if not all, commercial vehicle manufacturers but at various eras some manufacturers were less popular than others. The advent of Morris Commercial and a buy British campaign led to the replacement of Fords in the lighter vehicle groups by Morris Commercial and the production of vehicles specially designed for railway use by Dennis in the mid-thirties challenged but did not beat the almost universal LMS Morris Commercial light fleet. Karriers remained in favour throughout the LMS era but lost out to Albion in the heavier range. The giants Leyland and the AEC hardly had a look in but some off beat manufacturers were purchased in useful quantities, hatch, tractors, Jowett 15 cwt. vans and Reliant 5 cwt. three wheel vans. The Reliant vans seem to have been mainly allocated as low shed runabouts and most suffered an early and violent demise.

For modelling purposes the table below shows the typical sort of vehicles likely to be seen in the various periods.

| YEAR | LIGHT (under 2-ton) |

MEDIUM (2 to 4 ton) |

HEAVY (4 ton plus) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | Ford T | Karrier | Karrier ADC |

| 1930 | Morris Commercial Ford T |

Karrier Ford A |

Karrier ADC Albion |

| 1935 | Morris Commercial Dennis |

Karrier Scammel mech. horse Morris Commercial |

Albion Karrier ADC |

| 1940 | Morris Commercial Dennis Karrier |

Karrier Dennis Morris Commercial Scammel mech. horse |

Albion Karrier ADC |

Post 1940 anything going was purchased which led to new makes being taken into the fleet. The 'buses of the second World War also diminished the numbers of the old stalwarts like the heavy ADC's and Karriers so for the short period post-1945 the typical vehicles would be as 1940 but without the pre-1930 vehicles.

As has been previously stated the 1923 LMS vehicles were identical to the primitive Midland vehicles and continued as such for the next four or five years the comment of a crew transferred from a more or less weather proof L&Y or LNWR vehicle into a new open LMS vehicle must have been colourful in the extreme. This must eventually have filtered back to Derby because in the late twenties they started fitting windscreens. It is probably that they also supplied a conversion kit to convert existing models up to the new standards by the local maintenance depots. However, even in their final form the Derby designed LMS vehicles still looked Midland and archaic. Fortunately, Derby was pressed for space and the road motor centre was transferred to Wolverton where it remained until the end. The transfer took place about 1930 and there was an immediate transformation of all new LMS vehicles. The new cabs fitted were slight improvements of the LNWR designs which were soon updated by the provision of full height cab doors. This remained the standard design as long as standard cabs were being fitted to commercial chassis. Towards the end when most commercial vehicles were following the car style of "Stream-lining" the sloped back lines of the manufacturer and the very upright lines of the Wolverton cab conflicted rather badly but on the whole the Wolverton cab sat very well on most chassis. So far as lorry cabs were concerned both the Midland and the Wolverton style were altered as little as Possible from the standard to suit the various chassis.

When the heavier lorries came with driver's fittings set too far to the offside to suit the standard 4'6" wide cab, then the cab was offset to the offside to accommodate these fittings. There was one set of cabs which were neither Derby nor Wolverton standard designs, but if anything favoured the later L&Y designs. These were fitted to the ADC's and Leyland RAF types when they were completely rebuilt in the early thirties and provided with electric lighting, new wheels and pneumatic tyres.

Of course, during the twenties and thirties the vehicle manufacturers had made advances in vehicle designs both mechanical and otherwise. The most visually obvious advance was the provision of the pressed steel cab which was both cheaper and lighter than the wooden cab. In 1920 practically only Ford offered commercial vehicles complete with cabs but by 1940 practically no body offered a commercial without a cab. The LMS held out for a long time against using the standard manufacturer's cab. Some Ford A and B type lorries and some Morris Commercials in the C series were purchased and used complete with cabs but the first serious acquisition in fleet quantities to be made was the introduction of the Dennis 30 cwt. and 2 ton models in 1935 which came complete with manufacturer's cabs. The works type cab continued to be fitted beyond this date but it had more or less died a natural death before the Second World War completely finished it. The LMS continued to fit their own van and dray bodies as they had some very specialised requirements which were not met by the off the peg bodies. Delivery vans were provided with access from the cab to the van body so that they could be loaded from the back first-on first-off. Thus the driver could take his parcels from the front of the van all the time and never have to drop the tailgate during his delivery run - so the theory ran at any rate. It implied all sorts of working conveniences and efficiencies but is rather destroyed by my recollection that the usual riding position for the van boy was on the tailboard which was chained permanently open to the horizontal position. At any rate, the LMS were sufficiently in love with the theory that they modified manufacturer's standard cabs to give direct access to the van bodies. So far as drays were concerned the LMS considered them vulnerable to damage (which they are) and so made them quickly interchangeable. LMS drays were built as a self-supporting unit and fixed to the chassis with U bolts. If the dray was damaged then unbolt, lift off, replace and bolt up. The whole vehicle was not immobilised while repairs were carried out on the dray. This had a side benefit that the body could also easily be changed for special duties lift off a flat and replace with a livestock body. For these reasons most of the B suffix group of vehicles carry two fleet numbers one for the chassis unit and one for the body unit.

The LMS road motor engineers were responsible as had been their pre-group forebears for developing the utility of road motor transport. The L&Y stand dray system was adopted for handling efficiency at the outset but this was obviously not the ultimate solution to the problem and further ideas were investigated. The first experiments were based on a converted horse cart as a semi-trailer and a cut down Morris car as a tractor. This as an experiment proved to be abortive but when the car tractor was replaced with a three wheeled Platform powered trolley then things began to look more hopeful. Then by coincidence Karriers in 1930 introduced a light three wheeled chassis intended for refuse vehicles operating in restricted lanes and back alleys which were too narrow for conventional vehicles. This chassis was purchased and adapted for use as a tractor and the first mechanical horse introduced in 1931. The coupling was railway designed and known as the "Wolverton" coupling. In a way it was similar to the stand-dray system in that the tractor chassis carried two channels and the turn table of the semi trailer carried two sets of rollers. Both the channels and the rollers were inclined and the front end of the semi-trailer was supported when uncoupled by a pair of fixed (i.e. non-retractable) jockey wheels. In operation, the tractor backed up to the semi trailer and the rollers engaged in the channels, as the rollers went up the inclined channels this raised the front of the trailer until and 'Triang' type coupling locked the tractor and trailer together as one unit. To reverse the process the coupling catch was held off by a mechanical linkage and the tractor driven away thus dropping the trailer's front and back onto the jockey wheels. The trailer brakes were coupled to a spring loaded plate in the centre pivot of the turntable so that they were normally held on. When coupled to the tractor a second operated as linkage which pushed a pin up through the pivot point and forced the plate back against the spring thus releasing the trailer brakes or applying them when the second hand brake was pulled on. This coupling although crude worked well and was immediately put into service, not only by the LMS but also other railways and even purely road haulage firms. The engineering firm of Napiers saw the potential of an automatic coupling and uncoupling semi-trailer outfit and put into hand a series of refining experiments which ultimately in 1932 resulted in a rather superior coupling being produced. The patents of this coupling were sold off to Scammells and this is the coupling still in use today. Karriers as well also produced a varient of the Wolverton coupling but this was not generally adopted. The LMS used its own Wolverton coupling and the Scammell and Karrier mechanical horses. The Wolverton coupling was further-refined and in its final form had retractable inside jockey wheels. Although this removed some of the worst features of the original coupling its performance was not up to that of the Scammell coupling and in the post-Second World War era the Scammell unit became the accepted standard. The standard mechanical horse unit was a tractor and three trailers (one loading, one unloading and one in transit) of three tons capacity but there were some six ton units, still with three wheel tractors but sometimes Bedford, Dennis or Karrier four wheel tractors were used. Having achieved a solution to the handling problems the engineers had thoughts about the problems of manouvering vehicles in the restricted areas of both the railway premises and their customers' premises. The mechanical horse was even more manouverable than the horse and cart notwithstanding the fact that a horse can step sideways but there was a need for other vehicles besides mechanical horses. The railway was none too keen on the cab over engine layout which for a given dray length requires a shorter vehicle and, therefore, a shorter wheel base and tighter turning circle. The introduction by Dennis of a design where the engine was in front of the front axle was influenced by the railways' ideas. It did not materially shorten the vehicle but it did reduce the wheel base and thereby the turning circle. This in turn lead to a further vehicle design which was influenced by railway thinking. This time the problem to be solved was the work load of the vehicles crew. With a conventional cab mounted above the chassis everytime the crew mount they have to climb two or three feet up and climb down to dismount. This gets tiresome on local delivery work. To solve this problem the railway gave up its prejudices against cab-over-engine layouts and mounted the cab forward of the front wheel which enabled the cab to have a low walk-in floor. Both Karriers and Dennis produced this type of vehicle which were also used by other railways. The ultimate in LMS thinking for small local delivery vehicles was cab forward of front axle and engine mounted between the front and rear axle underneath the load space. A vehicle was produced to this ,specification by Scammell just before the War. Another one was supplied to the GWR and probably the other railways, for proving but the War interrupted this interesting experiment which has not been attempted since although other factors developed since have made it a much more practical proposition. Besides these quite major influences on vehicle design which affected the whole road transport industry, the LMS road motor department pioneered other minor but significant advances in vehicle design. One such instance was the provision of heavy moulded rubber wings to both front and back wheels. These wings were rigid enough to support headlights and other wing mountings but flexible enough to deflect when they fouled something and flex back into normal position when cleared. This scheme found popularity not only wit the railways but also with the C.P.O. who all continued to use it - until vehicles stopped having separate wing pressings.

This author has no proof but straws in the wind suggest that the Road Motor Engineers Department of the LMS was used as some sort of experimental test centre for all the railways. Many of the LMS's developments were adopted so quickly by the other railways that it seems there must have been some semi-official liaison between them. The railways all had their own Road Motor Departments with completely different policies but whereas the Karrier/Wolverton coupling mechanical horse was in use on all railways within the year of introduction as were the rubber wings, no other railway adopted the sliding cab door GWR/Thornicroft safety development which in its own right was a significant advance in vehicle design.

H.N. Twells and T.W. Bourne, A Pictorial Record of LMS Road Vehicles. OPC 1983 ISBN 0 86093 174 9