This site uses non-intrusive cookies to enable us to provide a better user experience for our visitors. No personal information is collected or stored from these cookies. The Society's policy is fully explained here. By continuing to use this site you are agreeing to the use of cookies.

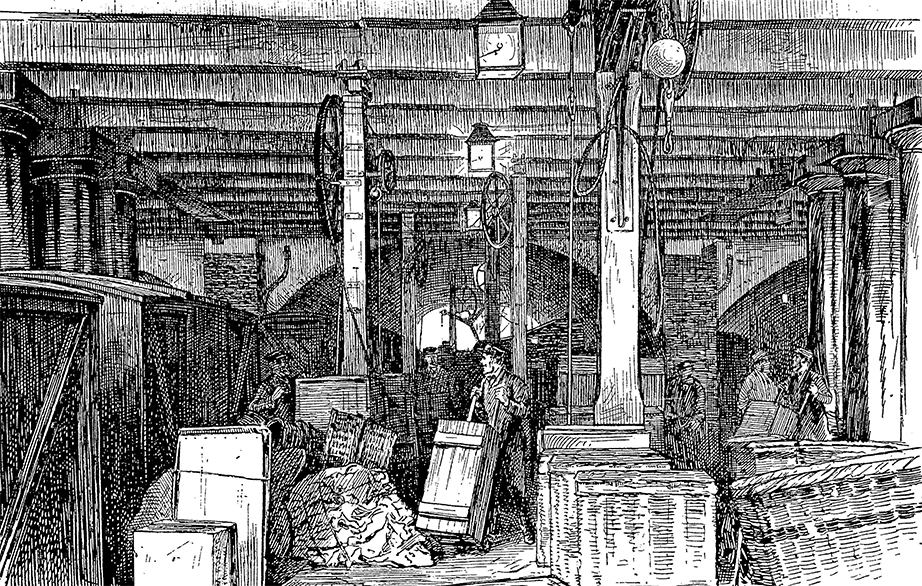

A "run" at Broad Street

At the first glance Broad Street Station looks much the same as London Road, except that it is on a larger scale throughout. As at Manchester, the goods station consists of a series of "runs" carried through the arches under the passenger station, and therefore at right angles to the passenger platforms. But there is a difference characteristic of the difference of the trade of the two places. Speaking broadly, Manchester only consigns goods directly to the outports, to London, and to the towns in its own neighbourhood; and these are a finite quantity. London, on the other hand, trades directly with every town in the kingdom. The subdivision is, therefore, too great for it to be possible for the vans to draw up as at Manchester, each opposite the row of trucks for which its goods are destined. Accordingly the goods are delivered on to the "bank" at one side of the station, and thence wheeled away on barrows to the train by which they are to be forwarded. Each "run" contains two trains, one on each side of the "bank," instead of a train and a cart road, as is the case at Manchester, And here comes in one of the problems with which the railway manager perpetually has to contend. "The more often. you handle your goods, the heavier will be your working expenses," is a cardinal maxim of railway policy. On the other hand, goods for Leeds or Liverpool must evidently be loaded and got away early, long before goods for Oxford or Rugby need be despatched, otherwise they will be too late for the first delivery next morning.

The public not being so obliging as to send in its Liverpool stuff at seven and keep back the "short norths", as they are termed, till nine, the unfortunate inspector is constantly between two fires; if he leaves his Oxford goods lying where the van deposited them till he wants to load them into their train, he blocks the "bank," and the men cannot do their work; if he attempts to load for every place at once, instead of employing 300 men for four hours he needs 400 men for three hours; and this, as he is well aware, means extra expense. At the end of each "run" is painted up the name of the train that is loaded in it, and each truck as it is finished is despatched to the upper air by the same method that has already been described as in use in Manchester, It may interest those who are concerned with the conditions and prospects of East End labour to know that some years back the North Western employed a considerable number of casual hands taken on at so much per hour. But the temptation to the men to prolong their work over as many hours as possible was too strong for them, and, as the arrangement consequently conduced neither to efficiency nor to economy, it has now been abandoned, and all the men at Broad Street are the regular servants of the Company.

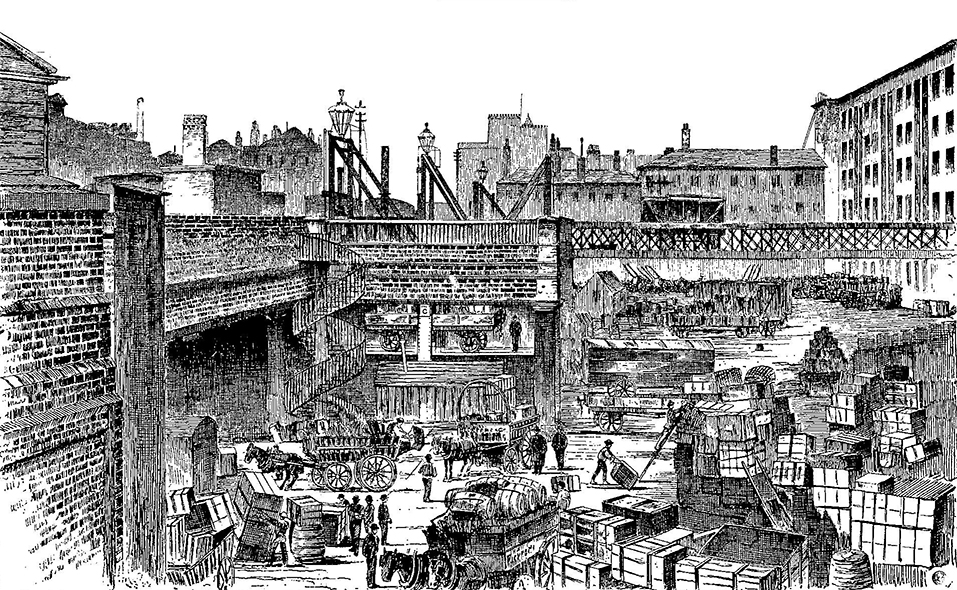

The "field" at Broad Street

Passing out of the "runs", we come to a space which, in comparison with the low-brewed arches we have left, is so open that it rejoices in the cheerful designation of "The Field." On one occasion we found "The Field" filled almost to overflowing with vast piles of empty cases, which our guide-mindful of the fact that, however many of them might come that way, the railway company at least got no profit out of them-not inaptly described as "wind."(1) Railway men have a knack of hitting out at times a happy phrase. "Birmingham feathers" is the latest addition to the Broad Street technical dictionary, the term being employed to designate the small iron scraps that, in the shape of tangled hanks of old wire, steel shavings, and so forth, make up some of the roughest and most awkward consignments that the servants of the Company are ever called upon to handle. On another occasion we noticed a very different state of things. There stood there five large vans, each containing five enormous rolls of paper. This we learnt was a two days' supply for one of the great London "dailies." It appears that almost all the newspapers get their paper from Lancashire, or in some cases from the. north of Ireland, via Broad Street, and that in the rail way warehouses there is always stored a supply sufficient for a fortnight's consumption, in case at any time there should be a break-down at the mills. If Carlyle could only have seen a whole archway filled with these" poor bits of rag paper" waiting to have" black ink printed on them "-not that by the way any large proportion of rags enter into the composition of the modern newspaper-still more if he could have climbed up, as we did, over the mountainous rolls and stood there with all their possibilities of wisdom beneath his feet, what a sermon would not the strangeness of his pulpit have suggested to him.

These immense rolls of paper require the utmost nicety in handling. The modern printing-press runs at such a tremendous pace that, unless the roll of paper is without a flaw, and unwinds absolutely true and square, it is liable in a moment to cause an accident. "At one time," said our informant, "we were always having complaints. We used to lift the rolls up with clamps to put them on the wagons. Then we tried passing a rod through the middle, but that pushed the edges out of the straight. Now we've got men who are accustomed to the work, and they sling each roll with a broad soft rope, and we never hear anything more about it."

But Broad Street is not content to deal only in "wind" and paper. On the contrary, its special distinction is the large proportion of "high class," or in other words profitable traffic. Of the fish, the meat, the butter, we have already spoken-we must just add that the dead-meat trade from Liverpool alone amounts to tens of thousands of tone in the year. Against this, which of course is into London, may be set the truck-loads of tea and of silk (insured for &50 or &100 each package), the hundreds upon hundreds of crates and boxes of drapery goods, the train-loads of wool (in those months when the wool sales are on), which leave the great warehouses in the City every night for every part of the country. "What is your busiest time in the year?" I asked. "Just before Easter," was the reply. The reason, which does not appear obvious at first sight, is as follows :- Easter is the accepted time for the purchaser of "summer novelties" in the drapery line. But the country shops put off laying in their summer stock till after Lady Day is past, so that they may not have to pay for the goods till Midsummer. Consequently between Lady Day and Easter the traffic comes with a rush, and when Easter falls early the rush is almost overpowering.

The trade of London has, no doubt, many remarkable peculiarities; but there can hardly be many features more remarkable than this, that, though London probably does not itself manufacture one ounce of all the tens of thousands of bales of wool that are poured into its port, almost all of it is carted up from the docks to warehouses in the heart of the City, and then carted back to the stations on its way to the West Riding or the Continent. The same might be said of the tea, the silk, and produce of all kinds. Everything is consigned to London, nothing is consigned via London to the towns beyond. Much the same thing, though not perhaps quite to the same extent, takes place with goods for export. Manchester or Halifax goods may be taken by the rail way companies straight through to the docks at Poplar or Millwall. But when they arrive there they are carted or lightered not direct to the ship's side, but to an adjacent warehouse, there to await the order of the manufacturer's London agent. It was perhaps the ignorance, or at least the neglect, of the cardinal fact that only a very small proportion-it has been put at one-thirteenth of the whole by one very competent authority-of the trade of London is transit trade that has led to the disastrous failure of the Tilbury Docks.

It is not quite true, by the way, to say that the traffic in eatables is only into London. Broad Street despatches every day to Lancashire three or four truck-loads of what is known as "offal" - the heads and feet, the hearts and livers of the animals that are slaughtered at the Deptford Cattle Market. But this may perhaps be considered to be balanced by the fact that there is also a large "inwards" traffic in cats-meat from Scotland. Why horses should die more freely in Scotland, or cats be more hungry in London, or why Lancashire should have a special penchant for tripe and trotters, is a sociological puzzle for which the Broad Street authorities have made no attempt to find a solution. They are satisfied to recognise the fact, and content if it bring some small accession of grist to the great North Western mill.

Let us notice one point more. In his recent lecture before the Royal Engineers at Chatham Mr. Findlay stated: "The staff of men and horses which this one Company alone employs in the collection and delivery of goods in London exceeds, I believe, the number required(2) to work all the coaches and vans that ran in former days to and from the North. We have altogether upwards of 2700 men and 640 horses engaged in the goods business in London, in addition to about the same number employed by Messrs. Pickford as our agents." Out of this regiment of heavy cavalry half are stabled under the arches of Broad Street ; and a strange sight - it is to look through one of them from side to side, along an: unbroken vista of backs and tails, for there are no stalls, and the animals are only separated from one another by swinging poles. Each horse has his own head-stall, with a number corresponding to that branded on his hoof, fixed up over his manger. And the horse-keepers not only say, but appear to believe, that the horse knows it; for they stoutly assert that if, after the horse's head-stall has been slipped and he has gone off to the water-troughs at the end of the arch, the number be shifted, the horse will go in search of it and refuse to return. For my own part, I can confirm the statement to this extent-that I certainly saw a horse refuse to return to his place. But then his number had not been changed, so I fear it hardly proves the truth of the story.(3)

Footnotes:

Site contents Copyright © LMS Society, 2026

February 12th, 2026

Site contents Copyright © LMS Society, 2026